Sadly I have to report that I haven’t yet found a way out of this disturbing parallel universe. Meanwhile this dark version of history keeps getting worse. I don’t have words to describe the baleful destruction, divisiveness and stupidity playing out on both sides of the Atlantic at the moment.

Instead I’ve found a hiding place, though it’s not perfect. News of various dystopian events keeps leaking through. But I’m trying to stay here and hide my head in books for as long as possible.

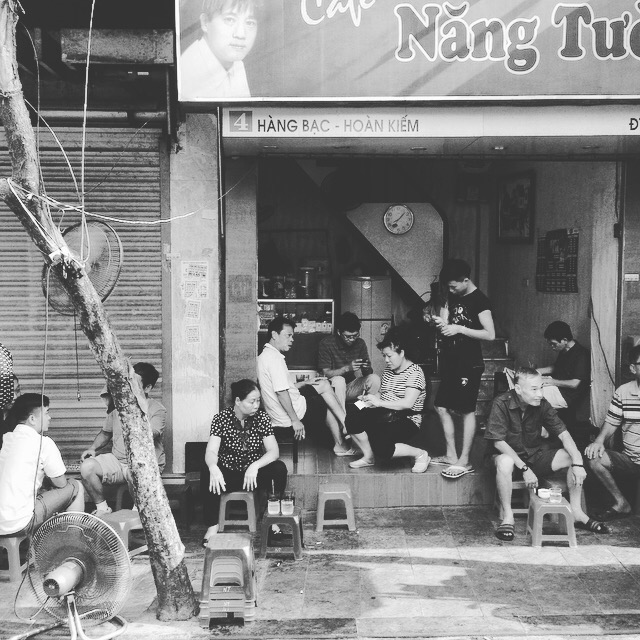

Back when I was in Hanoi I felt a similar desire to hide from a chaotic world. Once, when I was trying to cross a wide, busy road by the lake, I simply gave up and retreated into a nearby café instead.

The staff greeted me with a wholly un-Vietnamese level of enthusiasm. Unlike the other Southeast Asian countries I visited, I found that on the whole Vietnamese people were less ready to smile, and often spoke with a sort of abrupt familiarity bordering on rudeness. Paradoxically this made me like them all the more. It reminded me of Russia, where people go out of their way to help you whilst bossing you around in a hectoring, peremptory tone. The classic example is when a Russian lady in Moscow refused to believe I didn’t have the right change until she snatched up my purse and tipped all the money out to count it. Courtesy is all very well but it’s also quite othering. I felt less alien, more at home, in Vietnam than anywhere else in that part of the world.

At some point in the past Vietnam taxed buildings based on the width of the street frontage. This resulted in a weird architecture of long, thin buildings shaped like cereal boxes, with the thinnest side presented to the street. The Note Café was in one of these buildings, made up of a small footprint and a lot of floors and stairs. You order on the ground floor and are ushered up to sit in one of the rooms above.

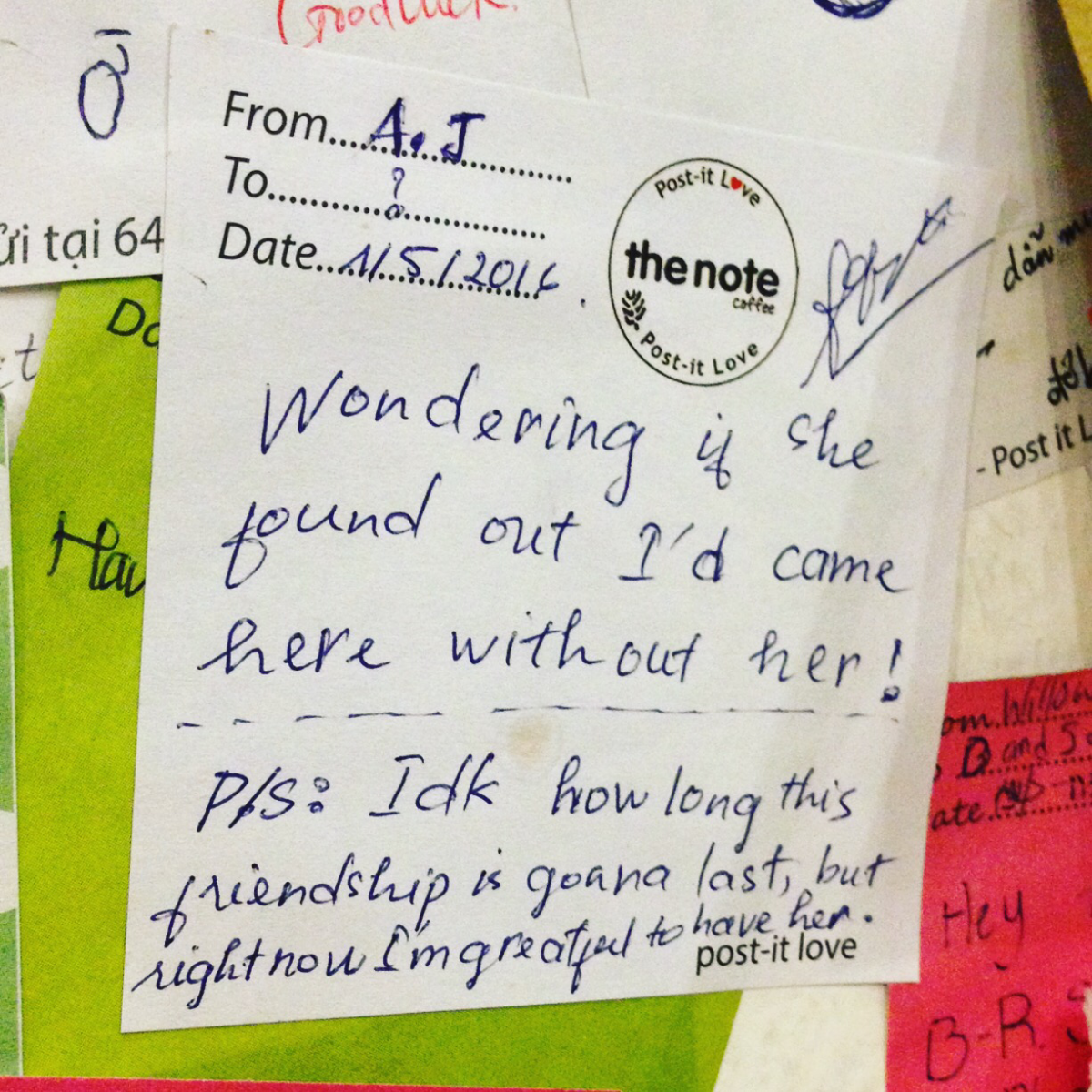

As I puffed up the steep stairs I realised I’d inadvertently stumbled into a very unusual establishment. The whole café is covered in colourful notes, plastered all over the walls, the windows, the doors, the chairs and tables and even the light fittings, all offering up brief messages from past visitors. The effect is overwhelming. Over time hundreds of messages have built up into layers of little drawings, jokes, signatures, multilingual greetings, bad spellings, bland deepitudes, hopes, dreams, fears, heartfelt confessions and expressions of love.

Being a cynical, world-weary, tired traveller, still recovering from a horrendous sleeper bus trip (I told you not to ask me about it), my first thought was this is a gimmick. But as I sat there, sipping a glorious iced Vietnamese coffee, the sheer accumulation of messages won me round. How often, when you’re sitting somewhere, do you think about all the other people who have been there before you? The world contains almost seven and a half billion people. Hanoi has a population of seven and a half million, and over 800,000 people visited Vietnam last year. Most of the time people pass through places without leaving a trace, but here you could look around and see their presence – and more than that, you could glimpse their thoughts, their personalities, their hopes and dreams fluttering on the walls. I was moved to see how many people used the ephemeral anonymity of a Post-It to unburden themselves to a community of equally transient souls.

Then, several weeks and adventures later, I found myself in the Mahamuni Pagoda in Mandalay, Burma, sitting on the floor and drinking some vile and violently blue ‘lemonade’. People kept coming up to talk to me while I sat there, including a strange self-important monk who offered to give me a tour of the place in terms that made it clear that it was not optional. He whizzed me round, telling me the age and weight in kilos of all the statues and gongs, ordering some small novices to recite something to me and finishing off by offering a long and bizarre blessing (“… and peace, good health, and don’t drink too much alcohol, and many happy returns.”)

This pagoda houses one of the three most holy Buddhist shrines in Burma, along with the golden stupa of the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon and the Golden Rock of Kyaiktiyo: the Mahamuni Buddha, a highly venerated golden statue. Men (though not women) can magnify the power of their prayers by applying a little square of gold leaf to it. Mandalay is therefore the centre of gold leaf production in Burma. I visited a traditional tourist trap of a factory while I was there.

Men hammered packets of gold into exquisitely thin, fragile leaf. It looked like hard work. Then, at the pagoda, other men carefully applied these slender leaves to the Mahamuni Buddha, praying all the while.

Over time, these devotions have altered the form of the statue itself, covered its most accessible parts in a thick layer of gold-leaf mounds, as if parts of it had been swathed in giant gold sheepskin. Gold bubbles out from the statue towards the kneeling worshippers before it, countless layers of shimmering devotions.

These two places where you can see the combined traces of our individual humanity have been on my mind ever since I visited them. They seem to say, even in the face of recent events: here we are. All of us, familiar and alien to each other, pinning up our thoughts on the walls for others to see; distorting the shape of the very things we worship with the layered weight of our fragile golden prayers.